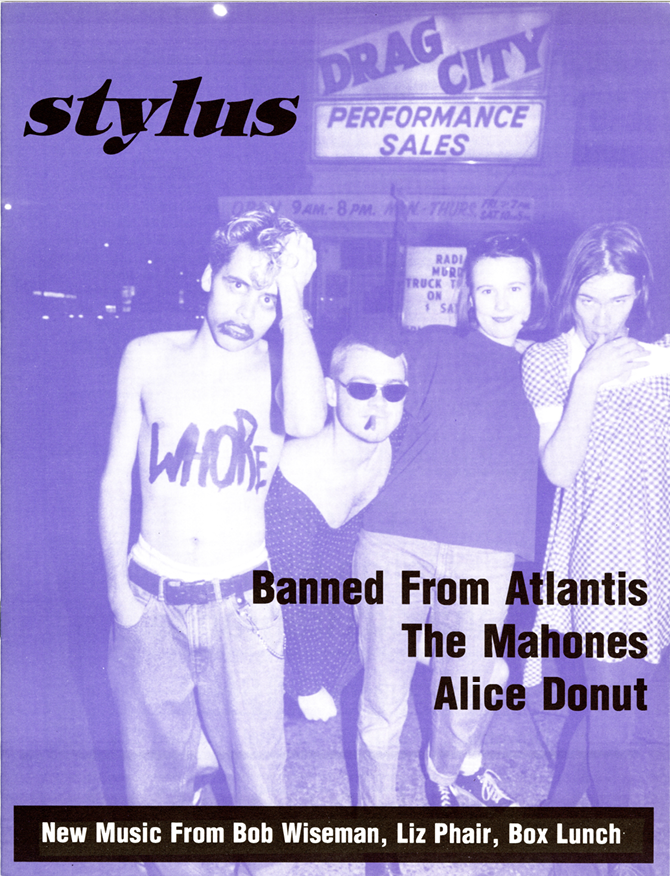

If you’re anything like me, you have an incorrigible fondness for what Walter Benjamin would call “[poking] about in the past as if rummaging in a storeroom of examples and analogies.” In which case: I am delighted to announce the good news. Stylus is saved!

I am speaking, of course, in retrospect. Our back catalogue has now been transferred to the University of Winnipeg Archives. Thanks to a provincial government heritage grant, I have been hired to digitize our old editions and to help make them viewable and searchable online.

I will spare you the silly, inside baseball terminological debate over whether the collection constitutes a standalone “Stylus Magazine fonds” or a single series within a conceptually larger “CKUW fonds.” As an archivist, I’m obliged not only to contemplate this sort of pedantic nonsense but to treat it with the utmost solemnity — but that doesn’t mean I need to inflict it on the greater reading public! For now, it should suffice to mention that, once I have finished processing the collection, it can be found under accession number 25.21. Remembering this number will come in handy if you ever decide you want to peruse the physical copies for yourself.

Now I’m sure many of you over the years have stumbled upon our Issuu page, where we’ve uploaded nearly every edition since 2008. Isn’t this an archive? Once the PDFs are online somewhere — problem solved, right?

Alas, digital objects are fragile things. If you’ve ever clicked on an intriguing hyperlink only to be redirected to a 404 page, you can attest to this yourself. Formats become obsolete. File names, URLs, entire websites can be changed or deleted on a whim. So, while there’s a lot of good stuff out there on the World Wide Web, there is no guarantee that any of it will survive in publicly accessible form indefinitely. Moreover, for-profit enterprises like Issuu do not have a mandate to preserve cultural heritage.

In theory, an archive’s raison d’être is to ensure that its holdings are acquired, arranged, and preserved with posterity in mind — that is, for the benefit not only of current users, but of future ones.

(In practice, however, one could be forgiven for pointing out that university archives, in the grand scale of time, are no more permanent than human lives or websites. But let’s keep things simple by ignoring that. To poke too many holes in the idea of “posterity” would defeat the entire purpose of archiving.)

So allow me to switch gears and briefly entertain the thought that any of this matters. I will do so by way of analogy.

In June 2001, the late Glenn Branca debuted his Symphony No. 13 at the World Trade Center in New York City. As his partner Reg Bloor later recounted, the process was highly chaotic: Branca started writing the piece a mere five weeks before its opening performance; it was composed for 100 guitarists, of whom only 85 showed up on the day of; and the symphony was so long and abrasive that a member of the ensemble was tasked with “giving a cue every ten measures for when the musicians lost their place.”

Although the performance seemed to go well — according to Bloor, it received a standing ovation — Branca wasn’t satisfied. He kept tinkering with the composition for years until finally a live recording was taken in Rome in 2008. By that point, the piece had been overhauled completely.

As Bloor put it: “That version has nothing in common with what we played in 2001. If you weren’t there, you didn’t hear it.”

My first response to reading this was to think “aw, rats!” My second response is to wonder: if the original performance of an acclaimed composer’s symphony did not survive to be reproduced, what hope do the rest of us have? How many more performances and compositions by lesser-known artists exist only, if at all, as foggy recollections fated for oblivion?

And so it is with our back catalogue. Beyond being a source of information (and, one hopes, entertainment), Stylus has produced invaluable documentary evidence of the Winnipeg alternative music scenes of the past four decades — even if only in textual and graphic form.

Hilary Jenkinson — an influential English archival theorist who has fallen out of favour in recent decades (for good reasons, though I decline to relitigate them here because, again, “inside baseball”) — was right about one thing. Record creators and archival researchers often do not have the same purposes in mind. The people who create the documents that are later scooped up by archives cannot anticipate how future historians will use or interpret their life’s work.

It is for this very reason that the project to archive Stylus is an important one for all the storeroom rummagers out there. While I can’t conceive of the research questions that might be answered by a 1999 review of a Guy Smiley show at the Horseshoe Cabaret, who’s to say what insights it might hold about the late-twentieth-century Winnipeg hardcore scene for a curious reader in 2099?

Or hell — why wait that long? Maybe you have some thoughts right now. If so, feel free to shoot me an email if you have any questions. I will note, however, that I’m still in the early stages of processing. Turns out that scanning 200-plus magazines, page by page, is going to take a while!

Maggie A. Clark is a retired Winnipeg lounge singer and inveterate joke thief.